*****

Sarah Shotland: Public transportation pops up again and again throughout Nine Kinds of Wrong. As someone who loves to write while riding public transportation, I'm curious if you also like to write while in transit? And what about public transportation inspires your work?

Colleen McKee: I’m blind in one eye. I have never driven a car in my life. That’s good because I spend every possible moment of my time that I am on public transit writing. Public transportation makes you get up close and personal with people you wouldn’t choose to know. In St. Louis, where I’m from, only the poor, disabled, and those with DUI’s ride the bus. Some of those buses are rip-roaring insane: people trying to sell you stolen socks, expired transfers, ripped-off movies, marijuana, Jesus Is Lord, candy bars…trying to get dates, trying to get you to be their 'ho…Lord have mercy, you name it. And all the while it stinks of piss. (I have a poem about the 70 Grand that appeared in my chapbook A Partial List of Things I Have Done for Money.)

Here in the Bay Area, almost everyone rides the BART train (Bay Area Rapid Transit). It’s this fascinating cross-section of our society, which is made up of thousands of different international, sexual, political, and artistic subcultures (plus yuppies). Add to this the very wide availability of potent drugs. And the fact that there’s at least one festival happening every day, so the chances are high you’re going to see someone covered in feathers, glitter, and not a lot else. Any writer should be able to get at least one poem off the BART every day—as long as her eyes aren’t glued to her phone. My bag is always full of postcards with drafts of poems on it. Maybe one day I’ll become the Premier Poet Laureate of BART.

Sarah: Can you talk a little bit about why you decided to include fiction, memoir and poetry in your collection?

Colleen: After Nine Kinds of Wrong came out, a successful writer told me, it was a terrible mistake that I had put these three genres together, that it made the book unmarketable. He said bookstores wouldn’t know how to promote it. But other writers say to me, “Wow, you can do that? I didn’t know you could get away with that. You’re lucky.” Readers who aren’t writers don’t comment on this at all.

I’ve always wanted my books to be fiction, poetry, and memoir mixed. My two chapbooks, My Hot Little Tomato and A Partial List of Things I Have Done for Money, were also a combination of poetry and prose. And within those books and chapbooks are a few stories that are hybrid forms, such as the poem “A Partial List of Things I Have Done for Money,” in which some of the lines are almost as long as paragraphs. It’s important to me to be able to mix these forms within a collection because I have some poems that I think of as sisters to certain works of memoir or fiction. For example, “What We Had Instead of History,” a poem, has much the same tone and topic as “How to Steal a Book.” They’re both sad, bratty pieces about being a juvenile delinquent. “How to Steal a Book” is a hybrid—it’s memoir with one stanza of a poem in the middle.

Sarah: How do you decide what material to present in a specific genre?

Colleen: It was more about atmosphere and intuition than genre. I knew it would be a grimy, sexy urban book, and that I would put in some more writing about Miko that hadn’t made it into my last chapbook, A Partial List of Things I Have Done for Money. (Miko was a close friend and old flame who killed himself in 2008.)

Sarah: What are the major differences you see between forms?

Colleen: For me there are no meaningful distinctions between these forms except, memoir should be true! In my work, line breaks are just a rhythmic device, like punctuation or a paragraph break.

Sarah: In "The 59 Cent Pad of Paper" you write (of a man in a mental institution): "What did he need from the paper? What could the paper give that man, who couldn't eat oatmeal without supervision? Each drug store pad of paper was a bird with sixty wings, all flapping at once. With each mark, he drew the wings closer to him, if only for a few scrawling seconds." I'm curious. What do you need from the paper? What does the paper give you?

Colleen: It is possibly a terrible, terrible weakness that I cannot understand the contents of my mind without a piece of paper to sort it all out. But often I am left with not understanding but only a sorrowful wonder. Or maybe just a feeling that whatever lonely wayward thing was gnawing at my heart has gone to sleep, at least for a while.

My experience of my life is very fragmented. I moved around a lot. I’ve cared for drifters and fools and friends who died young. I want a way to remember.

Sarah: I'm interested in the fine art of "perhapsing" in memoir. In the essay, "The Devil's Fruit" you explore your parents meeting. This essay reminded me a lot of Sharon Olds' poetry, specifically the poem "I Go Back to May, 1946." How do you deal with writing about events that you couldn't witness and how they affect your life?

Colleen: I think the only two stories I’ve written that I called memoir or nonfiction that I didn’t witness were stories my mom told me, “The Devil’s Fruit” and “The 59 Cent Pad of Paper.” My mom is a wonderful storyteller. In “The Devil’s Fruit,” I thought I was being accurate, but then Mom told me, “I didn’t meet your dad at high school. I met him at the Hamburger Doodle.” Even when I wrote a memoir about something I had lived through, “The Unbreakable House,” I made a mistake. The essay was about this all-metal house I lived in when I was eighteen. I wrote that it was gray, and my sister corrected me: It was baby blue! I remembered it as gray because I was so depressed when I lived there. So our memory quite literally colors our perception. As Borges wrote, “My memory is porous and the rain gets in.”

Yet I respect veracity, even if we can only approach it. The distinction between memoir and fiction is important to me: the author has an obligation to accuracy if she’s going to call it memoir. Ethically, she really has to try her best to be truthful. The only time I fudge is with dialogue because that is hard to remember verbatim, and memoirs that are light on dialogue can get dull. But even when I make up dialogue, I try to be close to what that person probably said. Maybe I write that my mom said, “Well now, I reckon she got a wild hair up her ass,” and what she really said was, “Oh Lord, what’s she hootin and hollerin about now?” Either way, it’s the sort of thing my mom would say, and they mean about the same. James Baldwin said, “I want to be an honest man and a good writer.” I’ve considered getting this tattooed on my arm.

Sarah: Your book swings between encounters with intimate lovers and intimate strangers. Where do you see the connection between these two kinds of encounters?

Colleen: Well, lovers can be strange, and strangers can certainly be intimate! Especially here in the Bay Area, where strangers can just let it all hang out. This is a place where newspapers are full of serious debates about whether it is permissible to be nude in a public plaza if you haven’t brought your own towel to sit on. But even more shocking to me, as a Midwesterner, are the things people will just tell you at a party, on the street. This is an endlessly fascinating place, to the point where it’s a little overwhelming. I have been writing a lot of poems lately about people on the train, on the street, parades, how the individual (including me) relates to the crowd or to intense strangers. Maybe my next book will be called The Teeming Masses: Insects and People on the Street. (I like insects, too. I write a lot about them.) It’s important for a writer to be willing to look closely at anyone with a gaze that is compassionate and curious—but also you have to watch your back. That’s a mixed urban feeling which is uncomfortable in life, but that tension can be interesting in writing.

James Joyce said, “To be is to live in mystery, not in understanding.” Sometimes I have written about lovers in an attempt to understand them, but probably my better love poems are the ones that were written in appreciation of their mystery.

Sarah: If I had to pluck an overarching theme from your book, I would point to grieving and loss. In addition to the characters and people you explore in the book, your "Thanks" section includes four RIPs, and the dedication includes an RIP. In "Real as a Loaf of Rye" you write: "When did it stop feeling strange to be haunted?" How does your work commune with the ghosts in your life? Do you feel an obligation to write for those who cannot read your work?

Colleen: Yes, a lot of RIP’s! In the last six years, in addition to losing my grandparents, I lost five friends, four of whom died young. Miko died of suicide. Roger was just found dead in his office, and Ray had the date rape drug in his body. Roger was a junkie and Ray was gay. My suspicion is, therefore, the cops didn’t care about them.

Do I have a responsibility to write for the dead? I don’t know. I believe we should remember the dead. That’s human. As a writer, I never feel I’ve fully engaged with a story or a memory until I’ve written it down. Do I have a responsibility to remember the dead the way they’d want to be remembered? If I only wrote about Miko in a way that I was one hundred percent certain he’d appreciate, I wouldn’t have written a word. He went in and out of the closet; he was moody; he drank; he was beautiful and sweet and my lover and my friend. I hope when I’m dead, people will remember me as I really am. I don’t want anyone to say, “Colleen was an angel.” I’d rather they said, “Colleen could really be a bitch. She could work your last nerve. But we had a lot of fun, and she wrote some good stories.”

Sarah: One of the most intimate portions of the book involves Miko. As readers, we meet him in the memoir section of the book, but we continue to explore your relationship in the following section of poetry. What was the process of writing about him? How do you revise and edit work that is so personal?

Colleen: What was the process of writing about Miko after his death? It was pure torture. But it was something I had to do. I wasn’t capable of distracting myself from the pain, so I wrote through it, every day. I was on a poetry postcard list—I sent a postcard every day to one of these people on a list. I was sending these depressing poems mostly to strangers! I can’t say if it was therapeutic. It was necessary. After Miko died, most people wanted to talk to me about it, a lot--for about two weeks! Then no one wanted to talk about it. There was a sense I was “dwelling” on it if I talked about him (or just burst out crying in public). But I needed to talk, and also, I needed to talk to him.

I don’t know how I edited the work about him. I did something that felt too hard for me to do, and somehow I’m still here.

*****

Find Colleen McKee's book here:

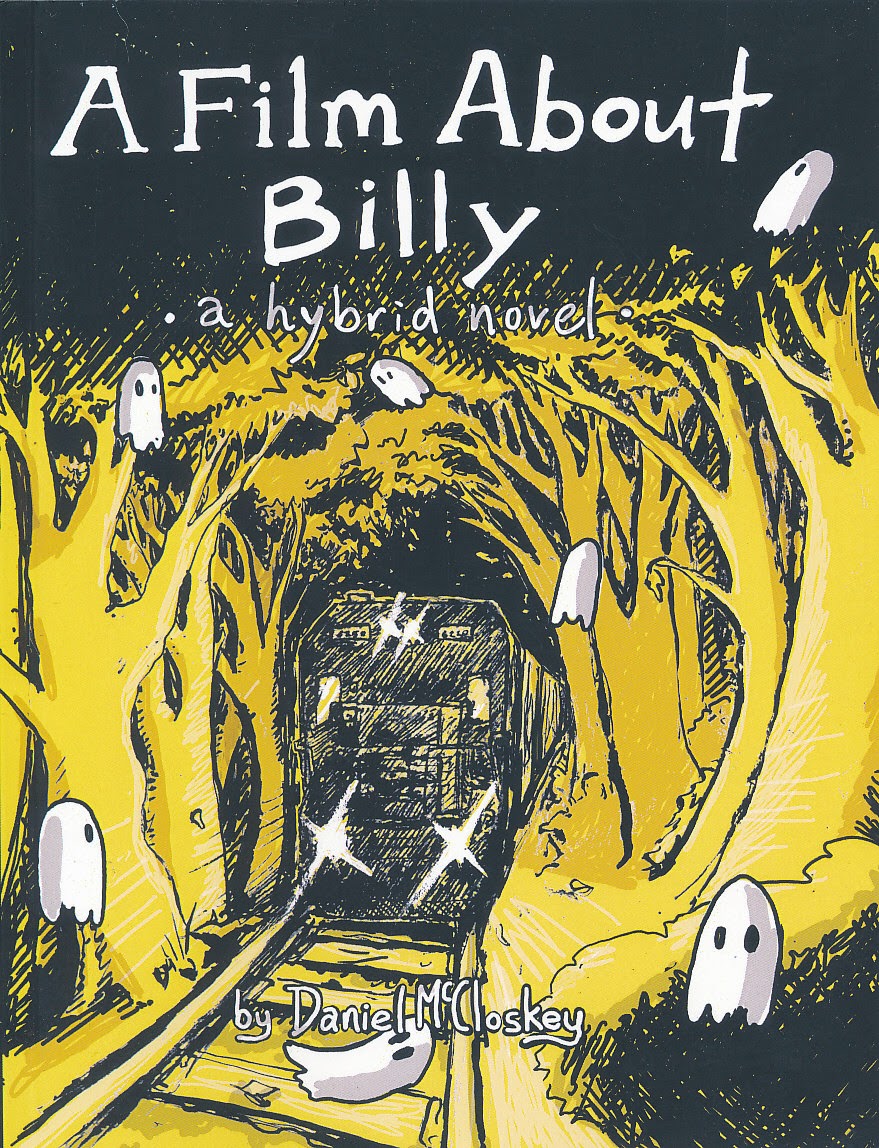

Find Sarah Shotland's novel here:

http://whitegorillapress.com/

http://whitegorillapress.com/

Earlier in the Writer on Writer series:

Two experimental writers from the same anthology, Wreckage of Reason Two:

Two novels about suicide epidemics:

Two novels about adjunct professors: