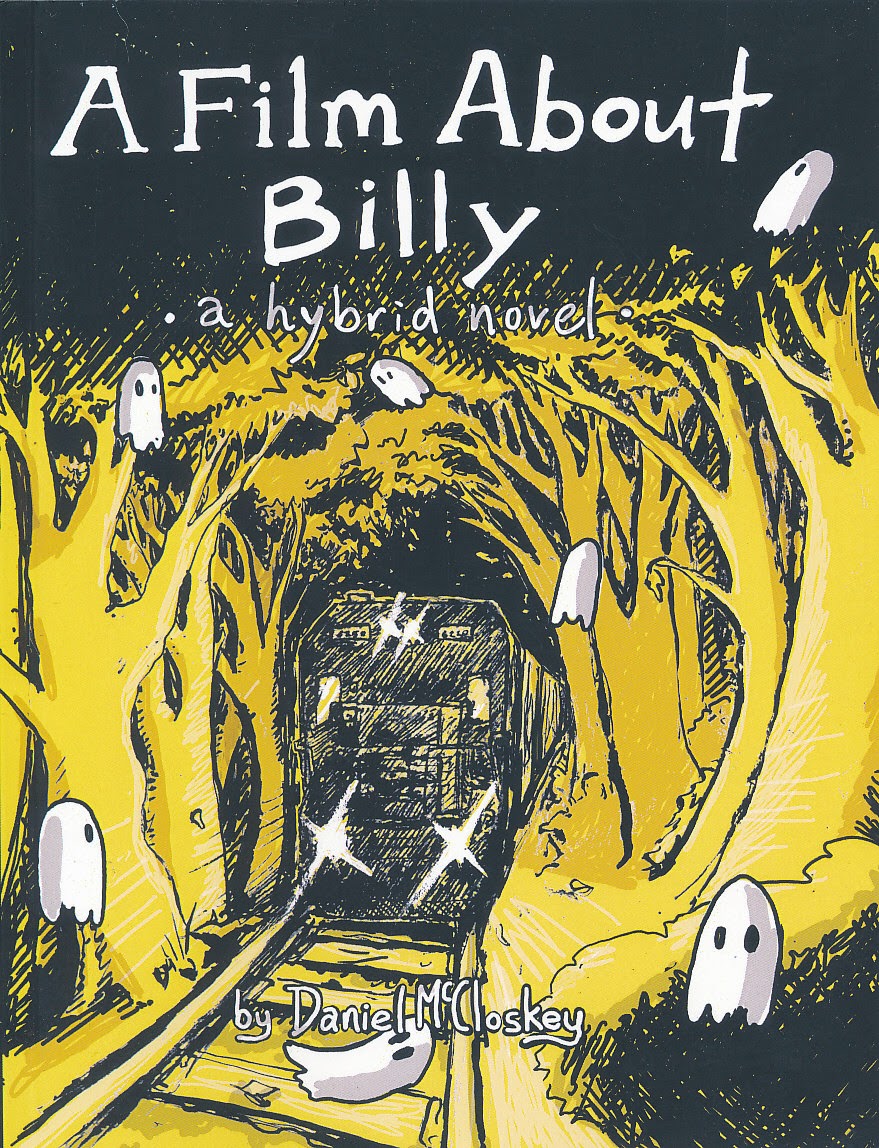

Following up on the last Writer on Writer interview, this week Bradley Spinelli interviews Daniel McCloskey. Bradley is author of Killing Williamsburg (Le Chat Noir) and Daniel wrote A Film About Billy (Six Gallery Press). Each 2013 novel follows a protagonist trying to outlive a suicide epidemic. At my suggestion, Bradley and Daniel read each other's books and came up with their own questions.

*****

Bradley Spinelli: I have to ask the obvious. Why a suicide epidemic?

Daniel McCloskey: At first it was in response to tragedy. I was 19. I heard, months after the fact, my friend had killed herself. She was the second friend of mine in two years to take their own life. Both did it before they turned 18. At the time I was dating someone that had been suicidal, and a number of people I knew had attempted or talked about it seriously. I wrote about a suicide epidemic because I thought there was one, and as it turns out there kind of is one. In Stephen Petranek’s TED talk,

10 Ways the World Could End Quickly, a depression epidemic makes the cut.

I also think apocalypse via suicide builds a dramatic image of the simple truth that we all die. While any apocalypse narrative has mass deaths, a suicide epidemic seemed to keep the focus on individuals and their deaths instead of the lava, the rain, the whatever that a protagonist might work against. The people that hurt you in a suicide epidemic are the victims, and they are already gone.

Bradley: I just read Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point last year. He talks about the teen suicide epidemic in Micronesia in the early ’80s. Did you know about that or did it have any influence?

Daniel: Yeah, I ran into The Tipping Point while I was studying abroad in Japan in 2007. That was also when I started putting comics into my book in earnest. Takashi Murakami’s Little Boy was a big deal for me at the time as well, the essays more than the art. I wasn’t sleeping a lot then--just walking around dark lonely Tokyo streets at night, and doing a lot of research in my University's English language library during the day.

Bradley: In your book the media pushes the epidemic, both in using the term “pandemic” to increase ratings and the very real idea that the media can spread the disease, that suicide can be just another meme. In writing Killing Williamsburg, I was taken by the fact that the New York Times doesn’t run stories on suicide. What’s your feeling? Should the media report suicides?

Daniel: I think what happens when a story about suicide is in the paper is that it opens up that possibility for people. It’s kind the opposite of, “If you can dream it you can be it.” It’s more like, “If you can’t imagine it you can’t do it.” So for someone who is predisposed towards suicide at the moment they see a suicide in the paper, suicide becomes an option in a concrete way. Yet suicide is no less the decision of the person who read about it in the paper than it is of the person written about in that article.

I tend to think we need to respect people’s ability to make decisions, even if we as individuals don’t really know why we do things. Do you know what I mean? Have you ever been in an argument with someone who’s hungry, and you know their anger has almost nothing to do with whatever your talking and has everything to do with a lack of food? I feel like in that case you need to respect that person’s feelings because those feelings are real, but we also need to address the underlying issue: hunger.

If suicides propagate every time a suicide is in the paper, I tend to believe that the problem isn’t the publicity but a deeper untreated depression issue that is illustrated by the fact that there are people walking around ready to off themselves once the thought occurs to them.

In Mexico, for example, suicide is publicized all the time in graphic detail, often with photographs, and the suicide rate in Mexico is less than half of the USA’s rate.

So, should the media report suicides? I don’t know.

As an author trying to orchestrate a suicide epidemic in your fictional world it seems that it would make the most sense to have the media ignore it while it begins, allowing the problem to snowball on its own in a localized environment (like in your book), then have the media pick it up when the suicides are at their peak. Because I do think that an environment where suicide becomes the norm might make it difficult to imagine the possibility of not killing yourself, especially for the young and impressionable. New York would be a great location to begin an American epidemic because the residents are from all over and have emotional connections to so many communities. There’s probably someone who loves someone in NYC in every corner of the planet.

Bradley: You describe A Film About Billy as a “hybrid novel”—half novel, half graphic novel. Did you ever consider doing the entire book as a graphic novel?

Daniel: When I began A Film About Billy the story was partially in screenplay format, but that format ultimately didn’t work for what I wanted to do. I learned to draw comics in order to make this book work, but I’ve always thought of it as primarily a prose novel. I am working on a comic series right now, Top of the Line, a monster fighting comic about a kid growing into a hero and in the process a terrible bigot. I’m enjoying that immensely, but I plan on going back to the hybrid format. Prose does something really different than comics and vice versa. As a story teller and an artist I get excited about the sheer unexplored possibility in comic prose hybrid work. Hopefully I’ll be announcing a new hybrid project in the summer.

Bradley: The book is paced really well. At the beginning, the present story is written and the past, which was videotaped, is drawn. This evolves, so that other segments of the story are drawn as the plotlines begin to diversify. How carefully did you plan what would be drawn and what would be written?

Daniel: To start, I just knew I wanted to use comics for the video tape “flashbacks,” but there were a couple of rules that worked themselves out for me really quickly. First, I didn’t want too many comic pages. I thought it was important to feel that the comics were speeding up the pace of a novel, instead of having a lot of text bogging down a comic. The prose is first person, so anything that I wanted to include in the story that Collin couldn’t see had to be in comic format. I also liked the idea of having more comics near the end of the story to add speed and intensity to the climax, so I added a page or two that could have been prose based on the other rules. That’s it. Basically I wrote and drew it together, so other versions had different comics as well as different text.

Bradley: The book starts out very naturalistic and becomes increasingly strange. The first mention of “weirdness” is experienced by Billy when he’s on shrooms, so we’re encouraged to dismiss it. But as the story becomes more fantastic your drawings also dabble in more dreamlike imagery. (You also introduce a talking Mr. Coffee.) How much of this book is intended to work on a subconscious level?

Daniel: I think that’s the whole ticket in fiction. We synthesize information into an emotional language so that our old monkey brains can digest it. Jung would talk about it as more of a bridge between the conscious and the subconscious, but it’s the same general idea. I think a lot of good fiction operates on a subconscious level without any weirdness, but that weirdness is what makes me me. I like to talk about serious issues through goat-eyed tigers, fighting robots, and talking coffee pots. I love Richard Brautigan and Dragon Ball Z, what can I say?

Bradley: Early on, all the gore happens off-screen, starting with Billy’s suicide and the great line, “When we learned what a train actually does to a body.” Even as the epidemic spreads, we only see a few suicides actually happen. It’s interesting to me, since I went so up-close and graphic in my book. How/why did you make this decision?

Daniel: I think that Collin didn’t really like thinking about how his friend died, even though that’s all he ever thought about. There were a lot of things he didn’t like thinking or talking about directly throughout the story. I tend to agree with a certain brand of literary artist who believes that the most powerful parts of a story are the parts that are unsaid, and having the deaths occur largely off screen gave them a certain weight in my mind.

Bradley: Overall, your book is much more concerned with male relationships—fathers and sons, and the brotherhood of friendship—than it is with women. But there are also buried details that suggest Billy was gay or bisexual. Why didn’t you investigate that further?

Daniel: That again was an issue of Collin not wanting to think (let alone openly talk) about his dead friend’s sexuality. I think that Collin has a real (and maybe accurate) impression that the omnipresent homophobic language and attitudes hurt his friend and contributed in some part to his eventual demise. Also, as an author I don’t give up much information about Billy at all. He is always there, but never fleshed out as a character. He is a ghost.

Bradley: Early on, Dan brought Billy back to life, so to speak, through the video for his funeral, yet Collin starts over. It’s obvious that you, as a writer, wanted to bring someone back to life in writing this book. Do you think it’s possible? Or did it at least help your own process of mourning, paying tribute, and moving on?

Daniel: You can’t bring someone back to life. You can’t even keep anyone alive. Everyone you know will die, and you will die. Again, that is the basic truth revealed in a suicide apocalypse.

Though I think there are certain truths humans will never stop needing to hear. We will die, love matters, greed kills, hubris makes and breaks our heroes, other people are whole other people, etc, etc. That’s why the one funeral in your book is so touching. You aren't burying “remains” when you bury your friend. You bury part of yourself. You’re giving your idea of them a place to go.

Bradley: The antagonists talk about gamma sync, and a cure for depression. I know gamma waves are often identified with mood and have also been discussed in relation to the binding problem. The theory that gamma waves can link information from all parts of the brain is a nice metaphor for the interconnectedness of the world that becomes a nightmare in your book. How invested were you in the science of the gamma profiling?

Daniel: I’m not very invested to be honest. Gamma sync was mostly a practical device for the sci-fi engine of the book, but I do think that mood and subtle mannerisms in our emotions may be the personhood that brings all our memories together. Even if you could download all the knowledge/memories in a brain you probably wouldn’t have that person without gluing a demeanor to it. I wanted these scientists to be working on something that they didn’t understand completely. The back story I constructed (but did not include) for the machine made gamma waves a plausible and potentially finicky element of the operation.

Bradley: The parallels between our books are downright eerie. Some stuff you just know, like that the National Guard would get involved. But in both our books the protagonist makes an appearance on TV—and don’t get me started on your book’s being titled after the character “Billy,” and mine after the neighborhood of Williamsburg, which is often called Billburg or Billyburg. (Shudder.) The part that made me jump up was when, after witnessing a suicide, Sarah tells Collin, “You’re not human.” I have virtually the same scene in my book when the protagonist is accosted by his girlfriend for being so cold. My wife likes to say that Benson is prepared for the suicide epidemic because he’s such an asshole, that thick skin is necessary in extreme conditions. What do you think?

Daniel: The TV thing is kind of a simple device to allow your character to give a speech, like right before battle in a war movie. It gives your character a moment to summarize the situation in their understanding, and show their true colors when the pressure’s on. I liked that part of your book. It was fun.

Maybe if there was a suicide epidemic a lot of people would accuse each other of not being human, or maybe it was again a good way for us as authors to say to our respective audiences, “Our character is different. Our character is alienated from the mainstream,” which we needed to say to make our characters largely ineligible for suicide. I for one didn’t want my readers to be wondering whether Collin would kill himself or not the whole time. I just didn’t want the story to be about that.

I had the same impression as your wife had about Benson. Collin isn’t as tough as Benson though. He’s alienated, and continues to alienate himself as a form of protection. He does his best not to get close to anyone in order to avoid being hurt by their eventual death. The problem, of course, is that Collin can’t help but care about his friends. That is why Mr. Coffee is so important. He’s the one friend Collin knows will never commit suicide. He’s a coffee pot, it’s just not possible for him to do anything, let alone kill himself.

Bradley: Both of our books feature a character telling another the simple answer: “Don’t kill yourself.” Do you think it’s really that simple?

Daniel: Well, no. I think suicide is really really complicated. But, at the same time I think that might be the right thing to say when you’re knee deep in a suicide epidemic. When Collin says something like that to Tyler in my book he’s empowering the kid who doesn’t feel like there are any options for him. To refer back to the question of publicizing suicide in the media--in a world where everyone is killing themselves a pre-teen with nobody left might not see any other options. Collin slapping Tyler on the back saying that he could make a point of being the last living person and stopping the epidemic hell or high water might just have been enough to save him. He could be the one, he could build tree forts on the top of the Empire State and howl at the moon. Ride horses through Disney Land... whatever. He’s just opening options in somebody else’s mind. I’m not saying, “If you can dream it, you can be it,” more like, “If you can’t even imagine it, you probably won’t find your way there.”

On the other hand at the very end Collin is being kind of a dick. He’s not even trying to find a cure, and maybe he could. He feels attacked by those who have killed themselves, and after all he was just killed by these people asking him questions. Saying “don’t kill yourself” in that context is kind of saying “fuck you.”

*****

Find A Film About Billy here

Don't miss Part One of this Writer on Writer: Daniel McCloskey Interviews Bradley Spinelli

Ealier in the Writer on Writer series:

Dave Newman Interviews Alex Kudera

Alex Kudera Interviews Dave Newman

Friday, March 14, 2014

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)